Invention (Patent Application Publication): Lang P,

Steines D, Bouadi H, Miller D. Minimally invasive joint implant with

3-dimensional geometry matching the articular surfaces. US20040133276A1 (2004).

Inventors: Philipp Lang, Daniel Steines, Hacene Bouadi, David Miller, Barry Linder, Cecily Snyder

Current Assignee: Conformis Inc

Application US10/681,750 events:

First worldwide family litigation filed

2003-10-07 Application filed by Imaging Therapeutics Inc

2003-10-07 Priority to US10/681,750

2004-07-08 Publication of US20040133276A1

Status: Abandoned

Minimally invasive joint

implant with 3-dimensional geometry matching the articular surfaces.

Philipp Lang, Daniel

Steines, Hacene Bouadi, David Miller, Barry Linder, Cecily Snyder

Abstract

This

invention is directed to orthopedic implants and systems. The invention also

relates to methods of implant design, manufacture, modeling and implantation as

well as to surgical tools and kits used therewith. The implants are designed by

analyzing the articular surface to be corrected and creating a device with an

anatomic or near anatomic fit; or selecting a pre-designed implant having

characteristics that give the implant the best fit to the existing defect.

Description

CROSS-REFERENCE TO RELATED APPLICATIONS

[0001]

This application

claims priority to U.S. Provisional Patent Application 60/416,601

filed by Philipp Lang on Oct. 7, 2002 for “Minimally Invasive Joint Implant

with 3-Dimensional Geometry Matching the Articular Surfaces” and

U.S. Provisional Patent Application 60/467,686 filed by Philipp Lang,

Daniel Steines, Hacene Bouadi, David Miller, Barry J. Linder, and Cecily Anne

Snyder for “Joint Implants” on May 2, 2003.

FIELD OF THE

INVENTION

[0002]

This invention is

directed to orthopedic implants and systems. The implants can be joint implants

and/or interpositional joint implants. The invention also relates to methods of

implant design, manufacture, modeling and implantation as well as to surgical

tools and kits used therewith. This invention also relates to a self-expandable

orthopedic implant amendable to arthroscopic insertion and profile alteration.

Finally, this invention is related to joint implants that are shaped such that

the implants re-establish normal, or near normal, 3D articular geometry or

alignment and facilitate joint movement that exceeds from 60 to 99.9% of the

normal range of motion for the joint and which are capable of withstanding up

to 100% of the normal shear force exerted on the joint during motion.

BACKGROUND OF THE

INVENTION

[0003]

There are various

types of cartilage, e.g., hyaline cartilage and fibrocartilage. Hyaline

cartilage is found at the articular surfaces of bones, e.g., in the joints, and

is responsible for providing the smooth gliding motion characteristic of

moveable joints. Articular cartilage is firmly attached to the underlying bones

and measures typically less than 5 mm in thickness in human joints, with

considerable variation depending on the joint and more particularly the site

within the joint. In addition, articular cartilage is aneural, avascular, and

alymphatic. In adult humans, this cartilage derives its nutrition by a double

diffusion system through the synovial membrane and through the dense matrix of

the cartilage to reach the chondrocyte, the cells that are found in the

connective tissue of cartilage.

[0004]

Adult cartilage has

a limited ability of repair; thus, damage to cartilage produced by disease,

such as rheumatoid arthritis and/or osteoarthritis, or trauma can lead to

serious physical deformity and debilitation. Furthermore, as human articular

cartilage ages, its tensile properties change. Thus, the tensile stiffness and

strength of adult cartilage decreases markedly over time as a result of the

aging process.

[0005]

For example, the

superficial zone of the knee articular cartilage exhibits an increase in

tensile strength up to the third decade of life, after which it decreases

markedly with age as detectable damage to type II collagen occurs at the

articular surface. The deep zone cartilage also exhibits a progressive decrease

in tensile strength with increasing age, although collagen content does not

appear to decrease. These observations indicate that there are changes in

mechanical and, hence, structural organization of cartilage with aging that, if

sufficiently developed, can predispose cartilage to traumatic damage.

[0006]

Usually, severe

damage or loss of cartilage is treated by replacement of the joint with a

prosthetic material, for example, silicone, e.g. for cosmetic repairs, or

suitable metal alloys. See, e.g., U.S. Pat. No. 6,383,228 to Schmotzer, issued

May 7, 2002; U.S. Pat. No. 6,203,576 to Afriat, et al., issued Mar. 20, 2001;

U.S. Pat. No. 6,126,690 to Ateshian et al., issued Oct. 3, 2000. Implantation

of these prosthetic devices is usually associated with loss of underlying

tissue and bone without recovery of the full function allowed by the original

cartilage and, with some devices, serious long-term complications associated

with the loss of significant amount of tissue and bone can include infection,

osteolysis and also loosening of the implant.

[0007]

As can be

appreciated, joint arthroplasties are highly invasive and require surgical

resection of the entire, or a majority of the, articular surface of one or more

bones involved in the repair. Typically with these procedures, the marrow space

is fairly extensively reamed in order to fit the stem of the prosthesis within

the bone. Reaming results in a loss of the patient's bone stock and over time

osteolysis will frequently lead to loosening of the prosthesis. Further, the

area where the implant and the bone mate degrades over time requiring the

prosthesis to eventually be replaced. Since the patient's bone stock is

limited, the number of possible replacement surgeries is also limited for joint

arthroplasty. In short, over the course of 15 to 20 years, and in some cases

even shorter time periods, the patient can run out of therapeutic options

ultimately resulting in a painful, non-functional joint.

[0008]

The use of matrices,

tissue scaffolds or other carriers implanted with cells (e.g., chondrocyte,

chondrocyte progenitors, stromal cells, mesenchymal stem cells, etc.) has also

been described as a potential treatment for cartilage repair. See, also,

International Publications WO 99/51719 to Fofonoff published Oct. 14, 1999; WO

01/91672 to Simon et al., published Dec. 6, 2001; and WO 01/17463 to Mansmann,

published Mar. 15, 2001; and U.S. Pat. No. 6,283,980 B1 to Vibe-Hansen, et al.,

issued Sep. 4, 2001; U.S. Pat. No. 5,842,477 to Naughton, et al., issued Dec.

1, 1998; U.S. Pat. No. 5,769,899 to Schwartz, issued Jun. 23, 1998; U.S. Pat.

No. 4,609,551 to Caplan et al., issued Sep. 2, 1986; U.S. Pat. No. 5,041,138 to

Vacanti et al., issued Aug. 20, 1991; U.S. Pat. No. 5,197,985 to Caplan et al.,

issued Mar. 30, 1993; U.S. Pat. No. 5,226,914 to Caplan, et al., issued Jul.

13, 1993; U.S. Pat. No. 6,328,765 to Hardwick et al., issued Dec. 11, 2001;

U.S. Pat. No. 6,281,195 to Rueger et al., issued Aug. 28, 2001; and U.S. Pat.

No. 4,846,835 to Grande, issued Jul. 11, 1989. However, clinical outcomes with

biologic replacement materials such as allograft and autograft systems and

tissue scaffolds have been uncertain since most of these materials cannot

achieve a morphologic arrangement or structure similar to or identical to that

of the normal, disease-free human tissue it is intended to replace. Moreover,

the mechanical durability of these biologic replacement materials remains

uncertain.

[0009]

U.S. Pat. No.

6,206,927 to Fell, et al., issued Mar. 21, 2001, and U.S. Pat. No. 6,558,421 to

Fell, et al., issued May 6, 2003, disclose a surgically implantable knee

prosthesis that does not require bone resection. This prosthesis is described

as substantially elliptical in shape with one or more straight edges. Accordingly,

these devices are not designed to substantially conform to the actual shape

(contour) of the remaining cartilage in vivo and/or the underlying bone. Thus,

integration of the implant can be extremely difficult due to differences in

thickness and curvature between the patient's surrounding cartilage and/or the

underlying subchondral bone and the prosthesis.

[0010]

Thus, there remains

a need for a system and method for replicating the natural geography of a joint

using one or more implant parts that can be implanted using minimally invasive

techniques and tools for making those repairs and implants and methods that

recreate natural or near natural three-dimensional geometric relationships

between two articular surfaces of the joint.

SUMMARY OF THE

INVENTION

[0011]

The present

invention provides methods and compositions for repairing joints, particularly

devices and implants useful for repairing articular cartilage and for

facilitating the integration of a wide variety of cartilage and bone repair

materials into a subject. Among other things, the techniques described herein

allow for the production of devices that substantially or completely conform to

the contour of a particular subject's underlying cartilage and/or bone and/or

other articular structures. In addition, the devices also preferably

substantially or completely conform to the shape (size) of the cartilage. When

the shape (e.g., size, thickness and/or curvature) of the articular cartilage

surface is an anatomic or near anatomic fit with the non-damaged cartilage,

with the subject's original cartilage, and/or with the underlying bone, the

success of repair is enhanced.

[0012]

The repair material

can be shaped prior to implantation and such shaping can be based, for example,

on electronic images that provide information regarding curvature or thickness

of any “normal” cartilage surrounding a defect or area of diseased cartilage

and/or on curvature of the bone underlying or surrounding the defect or area of

diseased cartilage, as well as bone and/or cartilage comprising the opposing

mating surface for the joint.

[0013]

The current

invention provides, among other things, for minimally invasive methods for

partial joint replacement. The methods can result in little or no loss in bone

stock resulting from the procedure. Additionally, the methods described herein

help to restore the integrity of the articular surface by achieving an anatomic

or near anatomic fit between the implant and the surrounding or adjacent

cartilage and/or subchondral bone.

[0014]

In most cases, joint

mobility for the repaired joint will range from 60 to 99.9% of normal mobility.

The range of motion is improved to 85-99.9%, more preferably between 90-99.9%,

most preferably between 95-99.9% and ideally between 98-99.9%.

[0015]

Further, the incisions

required to implant the devices of the invention typically are less than 50% of

the incision required to implant currently available implants. For example, a

total knee replacement typically employs an incision of from 6-12 inches (15-30

cm) while a unicompartmental knee replacement requires an incision of 3 inches

(7 cm). An implant according to this invention designed to repair the tibial

surface requires only a 3 cm incision (approximately 1.5 inches), while a

combination of implants for repairing both the tibial surface and the femoral

condyles requires an incision of 3 inches (7 cm). In another example, a

traditional hip replacement surgery requires a single incision of between 6 and

12 inches (15-30 cm), or in the less invasive technique two incisions of 1.5-4

inches (3-9.5 cm). An implant according to this invention designed to repair

the acetabulum requires a single incision of from 1.5 inches (3 cm) to 6 inches

(30 cm), depending upon whether single or dual surface correction is desired.

[0016]

Advantages of the

present invention can include, but are not limited to, (i) customization of

joint repair to an individual patient (e.g. patient specific design or

solution), thereby enhancing the efficacy and comfort level following the

repair procedure; (ii) eliminating the need for a surgeon to measure the defect

to be repaired intraoperatively in some embodiments; (iii) eliminating the need

for a surgeon to shape the material during the implantation procedure; (iv)

providing methods of evaluating curvature or shape of the repair material based

on bone, cartilage or tissue images or based on intraoperative probing

techniques; (v) providing methods of repairing joints with only minimal or, in

some instances, no loss in bone stock; and (vi) improving postoperative joint

congruity.

[0017]

Thus, the design and

use of joint repair material that more precisely fits the defect (e.g., site of

implantation) and, accordingly, provides improved repair of the joint is

described herein.

[0018]

As can be

appreciated by those of skill in the art an implant is described that is an

interpositional articular implant, cartilage defect conforming implant,

cartilage projected implant, and/or subchondral bone conforming implant. The

implant has a superior surface and an inferior surface. The superior surface

opposes a first articular surface of a joint and the inferior surface opposes a

second articular surface of the joint and further wherein at least one of the

superior or inferior surfaces has a three-dimensional shape that substantially

matches the shape of one of the first and second articular surfaces. The

implant is suitable for placement within any joint, including the knee, hip,

shoulder, elbow, wrist, finger, toe, and ankle. The superior surface and the

inferior surface of the implant typically have a three dimensional shape that

substantially matches the shape of at least one of the articular surface that

the superior surface of the implant abuts and the inferior surface of the

articular surface that the implant abuts. The implant is designed to have a

thickness of the cartilage defect in a patient, or a fraction thereof,

typically between 65% and 99.9%.

[0019]

The implant can be

manufactured from a variety of suitable materials, including biocompatible

materials, metals, metal alloys, biologically active materials, polymers, and

the like. Additionally, the implant can be manufactured from a plurality of

materials, including coatings.

[0020]

The implant can

further have a mechanism for attachment to a joint. Suitable attachment

mechanisms include ridges, pegs, pins, cross-members, teeth and protrusions.

Additional mechanisms for stabilization of the joint can be provided such as

ridges, lips, and thickening along all or a portion of a peripheral surface.

[0021]

The implant can also

be designed such that it has two or more components. These components can be

integrally formed, indivisibly formed, interconnectedly formed, and

interdependently formed, depending on the desired functionality. In the

multiple component scenario, the joint contacting components can be designed to

engage the joint slideably or rotatably, or a combination thereof.

Alternatively, either or both of the joint contacting components can be fixed

to the joint. Any additional components can be integrally formed, indivisibly

formed, interconnectedly formed or interdependently formed with any other

component that it engages.

[0022]

Each component of

the implant, or the implant itself can have a shape formed along its periphery

or perimeter that is circular, elliptical, ovoid, kidney shaped, substantially

circular, substantially elliptical, substantially ovoid, and substantially

kidney shaped. Additionally, each component of the implant, or the implant

itself can have a cross-sectional shape that is spherical, hemispherical,

aspherical, convex, concave, substantially convex, and substantially concave.

[0023]

The design of the

implant is such that it is conducive for implantation using an incision of 10

cm or less. Further, the implant is designed to restore the range of motion of

the joint to between 80-99.9% of normal joint motion.

[0024]

The implant, or any

component thereof, can have a variety of shapes such that the periphery of the

implant can be of greater thickness than a central portion of the implant. Alternatively,

the implant, or any component thereof, can be designed so that the central

portion of the implant is of greater thickness than a periphery. Looking at the

implant from a plurality of directions, such as an anterior portion, posterior

portion, lateral portion and medial portion, the implant, or any component

thereof, can have a thickness along the posterior portion of the device that is

equal to or greater than a thickness of at least one of the lateral, medial and

anterior portion of the implant. Alternatively, the implant, or any component

thereof, can have a thickness along a posterior portion of the device that is

equal to or less than a thickness of at least one of the lateral, medial and

anterior portion of the implant. In yet another alternative, the implant, or

any component thereof, can have a thickness along a medial portion of the

device that is equal to or less than a thickness of at least one of an anterior

portion, posterior portion, and lateral portion. In another alternative, the implant

can have a thickness along a medial portion of the device that is equal to or

greater than a thickness of at least one of an anterior portion, posterior

portion, and lateral portion.

[0025]

Procedures for

repairing a joint using the implant described below includes the step of

arthroscopically implanting an implant having a superior and inferior surface

wherein at least one of the superior or inferior surfaces has a

three-dimensional shape that substantially matches the shape of an articular

surface. The image can be analyzed prior to implantation. Typically the image

is an MRI, CT, x-ray, or a combinations thereof.

[0026]

The method of making

an implant according to this invention includes: determining three-dimensional

shapes of one or more articular surface of the joint; and producing an implant

having a superior surface and an inferior surface, wherein the superior surface

and inferior surface oppose a first and second articular surface of the joint

and further wherein at least one of the superior or inferior surfaces

substantially matches the three-dimensional shape of the articular surface.

[0027]

Further, the present

invention provides novel devices and methods for replacing a portion (e.g.,

diseased area and/or area slightly larger than the diseased area) of a joint

(e.g., cartilage and/or bone) with an implant material, where the implant

achieves an anatomic or near anatomic fit with at least one surface of the

surrounding structures and tissues and restores joint mobility to between

60-99.9% of the normal range of motion for the joint. Further, the implants can

withstand up to 100% of the shear force exerted on the joint during motion. In

cases where the devices and/or methods include an element associated with the

underlying articular bone, the invention also provides that the bone-associated

element can achieve an anatomic or near anatomic alignment with the subchondral

bone. The invention also enables the preparation of an implantation site with a

single cut. These devices can be interpositional. The devices can be single

component, dual component, or have a plurality of components.

[0028]

A method of the

invention comprises the steps of (a) measuring one or more dimensions (e.g.,

thickness and/or curvature and/or size) of the intended implantation site or

the dimensions of the area surrounding the intended implantation site; and (b)

providing cartilage replacement or material that conforms to the measurements

obtained in step (a). In certain aspects, step (a) comprises measuring the

thickness of the cartilage surrounding the intended implantation site and

measuring the curvature of the cartilage surrounding the intended implantation

site. Alternatively, step (a) can comprise measuring the size of the intended

implantation site and measuring the curvature of the cartilage surrounding the

intended implantation site; or measuring the thickness of the cartilage

surrounding the intended implantation site, measuring the size of the intended

implantation site, and measuring the curvature of the cartilage surrounding the

intended implantation site; or reconstructing the shape of healthy cartilage

surface at the intended implantation site; or measuring the size of the

intended implantation site and/or measuring the curvature or geometry of the

subchondral bone at the or surrounding the intended implantation site. In

addition, the thickness, curvature or surface geometry of the remaining

cartilage at the implantation site can be measured and can, for example, be

compared with the thickness, curvature or surface geometry of the surrounding

cartilage. This comparison can be used to derive the shape of a cartilage

replacement or material more accurately.

[0029]

The dimensions of

the replacement material can be selected following intraoperative measurements,

for example measurements made using imaging techniques such as ultrasound, MRI,

CT scan, x-ray imaging obtained with x-ray dye and fluoroscopic imaging. A

mechanical probe (with or without imaging capabilities) can also be used to

selected dimensions, for example an ultrasound probe, a laser, an optical

probe, an indentation probe, and a deformable material.

[0030]

One or more

implantable device(s) includes a three-dimensional body. In a knee, the implant

can be used in one (unicompartmental) or more (multicompartmental)

compartments. In the knee, the implant is not elliptical in shape, but follows

the 3D geometry of the articular cartilage, subchondral bone and/or

intra-articular structures. The implant has a pair of opposed faces. The

contours of one face of the implant matches or substantially match the

underlying cartilage and/or bone contour; while the contour of the opposing

face of the implant creates a surface for a mating joint surface to interface

with. For example, the surface of the opposing face can be projected using

modeling to optimize the surface for mating with the joint. In addition, the

opposed faces can be connected using a rounded interface. The interface can

also extend beyond the articular surface. The implants of the invention can

also be self-expandable and amendable to arthroscopic insertion.

[0031]

Each face of the

device is not necessarily uniform in dimension. The length D across one axis

taken at any given point is variable along that axis. Similarly the length 2D

across the second axis (perpendicular to the first axis) is also variable along

that axis as well. The ratio between any D length along a first axis and any D

length along a second axis can have any ratio that is suitable for the physical

anatomy being corrected and would be appreciated by those of skill in the art.

[0032]

As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, any of the implantable joint

prostheses described herein can comprise multiple (e.g., two or more pieces)

body components that are engageable (e.g., slideably) and/or separable without

departing from the scope of the invention. For example, a two-piece component

can be provided where each component has a face whose contour conforms,

partially or substantially, to the underlying cartilage and/or bone. In certain

embodiments, the opposing surfaces of the components that are engageable are

curved. The curvature can be selected to be similar to that or mirror that of

at least one articular surface for that joint. In other embodiments, the

opposing surfaces of the components that are engageable are flat. In other

embodiments, the opposing surfaces of the components that are engageable are a

combination of flat and curved. The opposing surfaces of the components that

are engageable can also be irregular. In this case, they are preferably

designed to mate with each other in at least one or more positions.

[0033]

In any of the

methods described herein, the replacement material can be selected (for

example, from a pre-existing library of repair systems). Thus, the replacement

material can be produced pre-, intra- or post-operatively. Furthermore, in any

of the methods described herein the replacement material can also be shaped

using appropriate techniques known in the art; either pre-operatively,

intra-operatively, or post-operatively. Techniques include: manually,

automatically or by machine; using mechanical abrasion including polishing,

laser ablation, radiofrequency ablation, extrusion, injection, molding, compression

molding and/or machining techniques, or the like. Finally, the implants can

comprise one or more biologically active materials such as drug(s), cells,

acellular material, pharmacological agents, biological agents, and the like.

[0034]

The invention

includes a method of repairing cartilage in a subject, the method comprising

the step of implanting cartilage repair material prepared according to any of

the methods described herein. Implantation is typically arthroscopic and can be

accomplished via a relatively small incision.

[0035]

The invention also

provides a method of determining the curvature of an articular surface, the

method comprising the step of intraoperatively measuring the curvature of the

articular surface using a mechanical probe or a surgical mechanical navigation

system. The articular surface can comprise cartilage and/or subchondral bone.

The mechanical probe (with or without imaging capabilities) can include, for

example an ultrasound probe, a laser, a mechanical arm (such as the Titanium

FARO arm) an optical probe and/or a deformable material or device.

[0036]

A variety of tools

can be used to facilitate the implantation of the devices. The tools are guides

that assist in optimally positioning the device relative to the articular surface.

The design of tools and guides for use with the devices is derived from the

design of the device suitable for a particular joint. The tools can include

trial implants or surgical tools that partially or substantially conform to the

implantation site or joint cavity.

[0037]

Any of the repair

systems or prostheses described herein (e.g., the external surface) can

comprise a polymeric material or liquid metal. The polymeric material can be

attached to a metal or metal alloy. The polymeric material can be injected and,

for example, be self hardening or hardening when exposed to a chemical, energy

beam, light source, ultrasound and others. Further, any of the systems or

prostheses described herein can be adapted to receive injections, for example,

through an opening in the external surface of the cartilage replacement

material (e.g., an opening in the external surface terminates in a plurality of

openings on the bone surface). Bone cement, therapeutics, and/or other

bioactive substances can be injected through the opening(s). In certain

embodiments, it can be desirable to inject bone cement under pressure onto the

articular surface or subchondral bone or bone marrow in order to achieve

permeation of portions of the implantation site with bone cement. In addition,

any of the repair systems or prostheses described herein can be anchored in

bone marrow or in the subchondral bone itself. One or more anchoring extensions

(e.g., pegs, etc.) can extend through the bone and/or bone marrow.

[0038]

In some embodiments,

the cartilage replacement system can be implanted without breaching the

subchondral bone or with only few pegs or anchors extending into or through the

subchondral bone. This technique has the advantage of avoiding future implant

“settling” and osteolysis with resultant articular incongruity or implant

loosening or other complications.

[0039]

As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, suitable joints include knee,

shoulder, hip, vertebrae, intervertebral disks, elbow, ankle, wrist, fingers,

carpometacarpal, midfoot, and forefoot joints, to name a few. The techniques

described likewise are not limited to joints found in humans but can be

extended to joints in any mammal.

[0040]

These and other

embodiments of the subject invention will be apparent to those of skill in the

art in light of the disclosure herein.

BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF

THE DRAWINGS

[0041]

FIG.

1 A is a block diagram of a method for assessing a joint in need of

repair according to the invention wherein the existing joint surface is

unaltered, or substantially unaltered, prior to receiving the selected implant.

FIG. 1B is a block diagram of a method for assessing a joint in need of

repair according to the invention wherein the existing joint surface is

unaltered, or substantially unaltered, prior to designing an implant suitable

to achieve the repair.

[0042]

FIG. 2 is a

reproduction of a three-dimensional thickness map of the articular cartilage of

the distal femur. Three-dimensional thickness maps can be generated, for

example, from ultrasound, CT or MRI data. Dark holes within the substances of

the cartilage indicate areas of full thickness cartilage loss.

[0043]

FIG.

3 A illustrates an example of a Placido disk of concentrically

arranged circles of light. FIG. 3B illustrates an example of a projected

Placido disk on a surface of fixed curvature.

[0044]

FIG. 4 shows a

reflection resulting from a projection of concentric circles of light (Placido

Disk) on each femoral condyle, demonstrating the effect of variation in surface

contour on the reflected circles.

[0045]

FIG. 5 illustrates

an example of a 2D color-coded topographical map of an irregularly curved

surface.

[0046]

FIG. 6 illustrates

an example of a 3D color-coded topographical map of an irregularly curved

surface.

[0047]

FIG.

7 A-B are block diagrams of a method for assessing a joint in need of

repair according to the invention wherein the existing joint surface is altered

prior to receiving implant.

[0048]

FIG.

8 A is a perspective view of a joint implant of the invention

suitable for implantation at the tibial plateau of the knee joint. FIG.

8B is a top view of the implant of FIG. 8A. FIG. 8C is a

cross-sectional view of the implant of FIG. 8B along the lines C-C shown

in FIG. 8B. FIG. 8D is a cross-sectional view along the lines D-D shown in

FIG. 8B. FIG. 8E is a cross-sectional view along the lines E-E shown in

FIG. 8B. FIG. 8F is a side view of the implant of FIG. 8A. FIG. 8G is

a cross-sectional view of the implant of FIG. 8A shown implanted taken

along a plane parallel to the sagittal plane. FIG. 8H is a cross-sectional

view of the implant of FIG. 8A shown implanted taken along a plane

parallel to the coronal plane. FIG. 8I is a cross-sectional view of the

implant of FIG. 8A shown implanted taken along a plane parallel to the

axial plane. FIG. 8J shows a slightly larger implant that extends closer

to the bone medially (towards the edge of the tibial plateau) and anteriorly

and posteriorly. FIG. 8K is a side view of an alternate embodiment of the

joint implant of FIG. 8A showing an anchor. FIG. 8L is a bottom view

of an alternate embodiment of the joint implant of FIG. 8A showing an

anchor. FIG. 8M and N illustrate alternate embodiments of a two

piece implant from a front view and a side view.

[0049]

FIG.

9 A and B are perspective views of a joint implant suitable

for use on a condyle of the femur from the inferior and superior surface

viewpoints, respectively. FIG. 9C is a side view of the implant of FIG.

9A. FIG. 9D is a view of the inferior surface of the implant; FIG.

9E is a view of the superior surface of the implant and FIG. 9F is a

cross-section of the implant. FIG. 9G is a view of the superior surface of

a joint implant suitable for use on both condyles of the femur. FIG. 9H is

a perspective side view of the implant of FIG. 9G.

[0050]

FIG.

10 A is a side view of the acetabulum. FIG. 10B is a rotated

view of the proximal femur. FIG. 10C is a cross-sectional view of an

implant for a hip joint showing a substantially constant radius.

[0051]

FIG.

10 D is a cross-sectional view of an implant similar to that seen in

FIG. 10C with a round margin and an asymmetric radius.

[0052]

FIG. 11 A is

a cross-sectional view of an implant with a member extending into the fovea

capitis of the femoral head. Additional and alternative plan views are shown of

FIG. 11B showing the implant as a hemisphere, a partial hemisphere FIG.

11C and a rail FIG. 11D FIG. 11E is a view of an alternative

embodiment of an implant with a spoke arrangement.

[0053]

FIG.

12 A is a cross-sectional view of an implant with a member extending

into the acetabular fossa. FIG. 12B-E illustrate a variety of perspective

views wherein the implant is hemispherical, partially hemispherical, a rail and

a spoke.

[0054]

FIG.

13 A is a cross-sectional view of a dual component “mobile bearing”

implant showing a two piece construction and smooth mating surfaces. Plan views

are also shown showing dual components with two hemispheres, single hemisphere

with a rail or rail-like exterior component (i.e., hemispherical in one

dimension, but not in the remaining dimensions), single hemisphere with rail

interior structure, single hemisphere with spoke interior component, and single

hemisphere with spoke exterior component.

[0055]

FIG.

13 B-J are alternative embodiments of a dual component implant where

the interior surface of the exterior component has a nub that engages with in

indent on the exterior surface of the interior component. Additional variations

are also shown.

[0056]

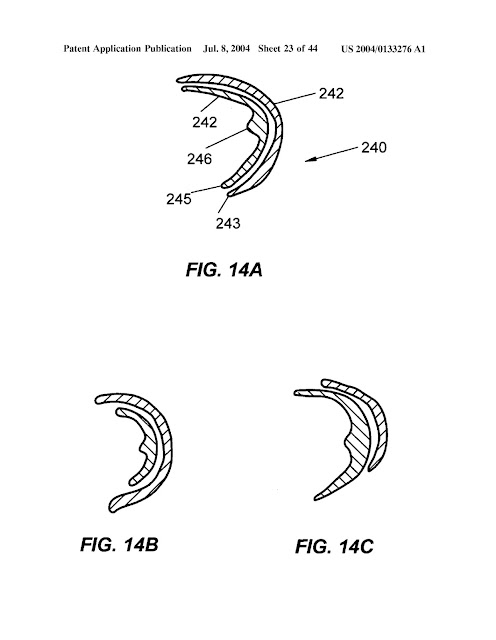

FIG.

14 A is an alternative embodiment of an implant with a member

extending into the fovea capitis of the femoral head. FIG. 14B and FIG.

14C show cross-sectional embodiments, where one of the components forms a

hemisphere while the second component does not.

[0057]

FIG.

15 A is a cross-sectional view of a dual component “mobile bearing”

implant with a member extending into the acetabular fossa. FIG. 15B and

FIG. 15C show cross-sectional embodiments, where one of the components

forms a hemisphere while the second component does not.

[0058]

FIG.

16 A is a cross-sectional view of a triple component “mobile bearing”

implant. FIG. 16B-D are cross-sectional views of a triple component

“mobile bearing” implant that have one or more components forming a hemisphere

while at least one other component does not.

[0059]

FIG.

17 A is a cross-sectional view of a dual component “mobile bearing”

implant with a member extending into the acetabular fossa. FIG. 17B and

FIG. 17C show cross-sectional embodiments, where one of the components

forms a hemisphere while the second component does not.

[0060]

FIG.

18 A is a cross-sectional view of a dual component “mobile bearing”

implant with a member extending into the acetabular fossa. FIG. 18B is a

view from the top showing four fins on top of the member shown in FIG.

18A extending into the acetabular fossa on top of the acetabular

component.

[0061]

FIG.

19 A is a cross-sectional view of a dual component “mobile bearing”

implant with a member extending into the fovea capitis of the femoral head.

FIG. 19B is a cross-sectional view of a dual component fixed implant.

[0062]

FIG.

20 A is a cross-sectional view of an implant with varying radii and

thickness for a hip joint. FIG. 20B is a cross-sectional view of an

implant with varying radii and thickness for a hip joint. FIG. 20C is a

cross-sectional view of an implant with varying radii and thickness for a hip

joint. FIG. 20D is a cross-sectional view of an implant for a hip joint

with a lip extending inferiorly and superiorly.

[0063]

FIG.

21 A is a frontal view of the osseous structures in the shoulder

joint such as the clavicle, scapula, glenoid fossa, acromion, coracoid process

and humerus. FIG. 21B is a view of an arthroplasty device placed between

the humeral head and the glenoid fossa. FIG. 21C is an oblique frontal

cross-sectional view of an arthroplasty device with the humeral surface

conforming substantially to the shape of the humeral head and the glenoid

surface conforming substantially to the shape of the glenoid. FIG. 21D is

an axial cross-sectional view of an arthroplasty device with the humeral

surface conforming substantially to the shape of the humeral head and the

glenoid surface conforming substantially to the shape of the glenoid. FIG.

21E is an oblique frontal view of the shoulder demonstrating the articular

cartilage and the superior and inferior glenoid labrum. FIG. 21F is an

axial view of the shoulder demonstrating the articular cartilage and the

anterior and posterior glenoid labrum. FIG. 21G is an oblique frontal

cross-sectional view of an arthroplasty device with the humeral surface

conforming substantially to the shape of the humeral head and the glenoid

surface conforming substantially to the shape of the glenoid and the glenoid

labrum. FIG. 21H is an axial cross-sectional view of an arthroplasty with

the humeral surface conforming substantially to the shape of the humeral head

and the glenoid surface conforming substantially to the shape of the glenoid

and the glenoid labrum. FIG. 21I is an oblique frontal cross-sectional

view of an arthroplasty device with the humeral surface conforming

substantially to the shape of the humeral head and the glenoid surface

conforming substantially to the shape of the glenoid. A lip is shown extending

superiorly and/or inferiorly which provides stabilization over the glenoid.

FIG. 21J is an axial cross-sectional view of an arthroplasty device with

the humeral surface conforming substantially to the shape of the humeral head

and the glenoid surface conforming substantially to the shape of the glenoid. A

lip is shown extending anteriorly and/or posteriorly which provides

stabilization over the glenoid. FIG. 21K is an oblique frontal

cross-sectional view of a dual component, “mobile-bearing” arthroplasty device

with the humeral surface conforming substantially to the shape of the humeral

head and the glenoid surface conforming substantially to the shape of the

glenoid.

[0064]

FIG.

21 L is an axial cross-sectional view of a dual component,

“mobile-bearing” arthroplasty device with a humeral conforming surface that

conforms to the shape of the humeral head and a glenoid conforming surface that

conforms to the shape of the glenoid. FIG. 21M is an alternate view of a

dual component, “mobile-bearing” arthroplasty device with a humeral conforming

surface that conforms to the shape of the humeral head and a glenoid conforming

surface that conforms to the shape of the glenoid. The device has a nub on the

surface of the first component that mates with an indent on the surface of the

second component to enhance joint movement.

[0065]

FIG.

21 N is an oblique frontal cross-sectional view of a dual component,

“mobile-bearing” arthroplasty device. FIG. 21O is an oblique frontal cross-sectional

view of a dual component, “mobile-bearing” arthroplasty device. FIG.

21P and Q are cross-sectional views of alternate embodiments of

the dual mobile bearing device shown in FIG. 21O.

[0066]

FIG. 22 is an

oblique longitudinal view through the elbow joint demonstrating the distal

humerus, the olecranon and the radial head. The cartilaginous surfaces are also

shown.

[0067]

FIG.

23 A is a longitudinal view through the wrist joint demonstrating the

distal radius, the ulna and several of the carpal bones with an arthroplasty

system in place. FIG. 23B is a longitudinal view through the wrist joint

demonstrating the distal radius, the ulna and several of the carpal bones with

an arthroplasty system in place. FIG. 23C is a longitudinal view through

the wrist joint demonstrating the distal radius, the ulna and several of the

carpal bones with an arthroplasty system in place. FIG. 23D is a

longitudinal view of a dual component, “mobile-bearing” arthroplasty device

suitable for the wrist. FIG. 23E is a longitudinal view of another dual

component arthroplasty device, in this case without lips. FIG. 23F is a

longitudinal view of a dual component, “mobile-bearing” arthroplasty device.

[0068]

FIG. 24 is a sagittal

view through a finger. An arthroplasty device is shown interposed between the

metacarpal head and the base of the proximal phalanx.

[0069]

FIG.

25 A is a sagittal view through the ankle joint demonstrating the

distal tibia, the talus and calcaneus and the other bones with an arthroplasty

system in place. FIG. 25B is a coronal view through the ankle joint

demonstrating the distal tibia, the distal fibula and the talus. An

arthroplasty device is shown interposed between the distal tibia and the talar

dome. FIG. 25C is a sagittal view through the ankle joint demonstrating

the distal tibia, the talus and calcaneus and the other bones. The

cartilaginous surfaces are also shown. An arthroplasty device is shown

interposed between the distal tibia and the talar dome. FIG. 25D is a

coronal view through the ankle joint demonstrating the distal tibia, the distal

fibula and the talus. An arthroplasty device is shown interposed between the

distal tibia and the talar dome.

[0070]

FIG. 26 is a

sagittal view through a toe. An arthroplasty device is shown interposed between

the metatarsal head and the base of the proximal phalanx.

[0071]

FIG.

27 A-D are block diagrams of method steps employed while implanting

an device of the invention into a target joint.

[0072]

FIG. 28 is a plan

view of an implant guide tool suitable for use implanting the device shown in

FIG. 8 L

[0073]

FIG.

29 A and B are a plan views of an implant guide tool

suitable for use implanting the device shown in FIG. 9B.

DETAILED DESCRIPTION

OF THE INVENTION

[0074]

The following

description is presented to enable any person skilled in the art to make and

use the invention. Various modifications to the embodiments described will be

readily apparent to those skilled in the art, and the generic principles

defined herein can be applied to other embodiments and applications without

departing from the spirit and scope of the present invention as defined by the

appended claims. Thus, the present invention is not intended to be limited to

the embodiments shown, but is to be accorded the widest scope consistent with

the principles and features disclosed herein. To the extent necessary to

achieve a complete understanding of the invention disclosed, the specification

and drawings of all issued patents, patent publications, and patent

applications cited in this application are incorporated herein by reference.

[0075]

As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, the practice of the present invention

employs, unless otherwise indicated, conventional methods of x-ray imaging and

processing, x-ray tomosynthesis, ultrasound including A-scan, B-scan and

C-scan, computed tomography (CT scan), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI),

optical coherence tomography, single photon emission tomography (SPECT) and

positron emission tomography (PET) within the skill of the art. Such techniques

are explained fully in the literature and need not be described herein. See,

e.g., X-Ray Structure Determination: A Practical Guide, 2nd Edition, editors

Stout and Jensen, 1989, John Wiley & Sons, publisher; Body CT: A Practical

Approach, editor Slone, 1999, McGraw-Hill publisher; X-ray Diagnosis: A

Physician's Approach, editor Lam, 1998 Springer-Verlag, publisher; and Dental

Radiology: Understanding the X-Ray Image, editor Laetitia Brocklebank 1997, Oxford

University Press publisher.

I. Dual or Multiple

Surface Assessment of the Joint

[0076]

The invention

allows, among other things, a practitioner to evaluate and treat defects to

joints resulting from, for example, joint disease, cartilage degeneration,

osteoarthritis, seropositive and seronegative arthritides, bone damages,

cartilage damage, trauma, and/or degeneration due to overuse or age. The size,

volume and shape of the area of interest can include only the region of

cartilage that has the defect, but preferably can also include contiguous parts

of the cartilage surrounding the cartilage defect. Moreover, the size, volume

and shape of the area of interest can include subchondral bone, bone marrow and

other articular structures, e.g. menisci, ligaments and tendons.

[0077]

FIG.

1 A is a flow chart showing steps taken by a practitioner in

assessing a joint. First, a practitioner obtains a measurement of a target

joint 10. The step of obtaining a measurement can be accomplished by

taking an image of the joint. This step can be repeated, as necessary, 11 to

obtain a plurality of images in order to further refine the joint assessment

process. Once the practitioner has obtained the necessary measurements, the

information is used to generate a model representation of the target joint

being assessed 30. This model representation can be in the form of a

topographical map or image. The model representation of the joint can be in

one, two, or three dimensions. It can include a physical model. More than one

model can be created 31, if desired. Either the original model, or a

subsequently created model, or both can be used. After the model representation

of the joint is generated 30, the practitioner can optionally generate a

projected model representation of the target joint in a

corrected condition 40. Again, this step can be repeated 41, as

necessary or desired. Using the difference between the topographical condition

of the joint and the projected image of the joint, the practitioner can then

select a joint implant 50 that is suitable to achieve the

corrected joint anatomy. As will be appreciated by those of skill in the art,

the selection process 50 can be repeated 51 as often

as desired to achieve the desired result.

[0078]

As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, the practitioner can proceed directly

from the step of generating a model representation of the target joint 30 to

the step of selecting a suitable joint replacement implant 50 as

shown by the arrow 32. Additionally, following selection of suitable joint

replacement implant 50, the steps of obtaining measurement of target

joint 10, generating model representation of target joint 30 and

generating projected model 40, can be repeated in series or parallel

as shown by the flow 24, 25, 26.

[0079]

FIG.

1 B is an alternate flow chart showing steps taken by a practitioner

in assessing a joint. First, a practitioner obtains a measurement of a target

joint 10. The step of obtaining a measurement can be accomplished by

taking an image of the joint. This step can be repeated, as necessary, 11 to

obtain a plurality of images in order to further refine the joint assessment

process. Once the practitioner has obtained the necessary measurements, the

information is used to generate a model representation of the target joint

being assessed 30. This model representation can be in the form of a

topographical map or image. The model representation of the joint can be in

one, two, or three dimensions. The process can be repeated 31 as

necessary or desired. It can include a physical model. After the model

representation of the joint is assessed 30, the practitioner can

optionally generate a projected model representation of the target joint of the

joint in a corrected condition 40. This step can be repeated 41 as

necessary or desired. Using the difference between the topographical condition

of the joint and the projected image of the joint, the practitioner can then

design a joint implant 52 that is suitable to achieve the

corrected joint anatomy, repeating the design process 53 as

often as necessary to achieve the desired implant design. The practitioner can

also assess whether providing additional features, such as lips, pegs, or

anchors, will enhance the implants' performance in the target joint.

[0080]

As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, the practitioner can proceed directly

from the step of generating a model representation of the target joint 30 to

the step of designing a suitable joint replacement implant 52 as

shown by the arrow 38. Similar to the flow shown above, following the

design of a suitable joint replacement implant 52, the steps of

obtaining measurement of target joint 10, generating model representation

of target joint 30 and generating projected model 40, can

be repeated in series or parallel as shown by the flow 42, 43, 44.

[0081]

The joint implant

selected or designed achieves anatomic or near anatomic fit with the existing

surface of the joint while presenting a mating surface for the opposing joint

surface that replicates the natural joint anatomy. In this instance, both the

existing surface of the joint can be assessed as well as the desired resulting

surface of the joint. This technique is particularly useful for implants that

are not anchored into the bone.

[0082]

FIG. 2 illustrates a

color reproduction of a 3-dimensional thickness map of the articular cartilage

of the distal femur. Thee-dimensional thickness maps can be generated, for

example, from ultrasound, CT, or MRI data. Dark holes within the substance of

the cartilage indicate areas of full thickness cartilage loss. From the

3-dimensional thickness map a determination can be made of the size and shape

of cartilage damage.

[0083]

As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, size, curvature and/or thickness

measurements can be obtained using any suitable technique. For example, one

dimensional, two dimensional, and/or in three dimensional measurements can be

obtained using suitable mechanical means, laser devices, electromagnetic or

optical tracking systems, molds, materials applied to the articular surface

that harden and “memorize the surface contour,” and/or one or more imaging

techniques known in the art. Measurements can be obtained non-invasively and/or

intraoperatively (e.g., using a probe or other surgical device). As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, the thickness of the repair device

can vary at any given point depending upon the depth of the damage to the

cartilage and/or bone to be corrected at any particular location on an articular

surface.

[0084]

A. Imaging

Techniques

[0085]

As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, imaging techniques suitable for

measuring thickness and/or curvature (e.g., of cartilage and/or bone) or size

of areas of diseased cartilage or cartilage loss include the use of x-rays,

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography scanning (CT, also known

as computerized axial tomography or CAT), optical coherence tomography, SPECT,

PET, ultrasound imaging techniques, and optical imaging techniques. (See, also,

International patent Publication WO 02/22014 to Alexander, et al., published

Mar. 21, 2002; U.S. Pat. No. 6,373,250 to Tsoref et al., issued Apr. 16, 2002;

and Vandeberg et al. (2002) Radiology 222:430-436). Contrast or other

enhancing agents can be used using any route of administration, e.g.

intravenous, intra-articular, etc.

[0086]

In certain

embodiments, CT or MRI is used to assess tissue, bone, cartilage and any

defects therein, for example cartilage lesions or areas of diseased cartilage,

to obtain information on subchondral bone or cartilage degeneration and to

provide morphologic or biochemical or biomechanical information about the area

of damage. Specifically, changes such as fissuring, partial or full thickness

cartilage loss, and signal changes within residual cartilage can be detected

using one or more of these methods. For discussions of the basic NMR principles

and techniques, see MRI Basic Principles and Applications, Second Edition, Mark

A. Brown and Richard C. Semelka, Wiley-Liss, Inc. (1999). For a discussion of

MRI including conventional T1 and T2-weighted spin-echo imaging, gradient

recalled echo (GRE) imaging, magnetization transfer contrast (MTC) imaging,

fast spin-echo (FSE) imaging, contrast enhanced imaging, rapid acquisition

relaxation enhancement, (RARE) imaging, gradient echo acquisition in the steady

state, (GRASS), and driven equilibrium Fourier transform (DEFT) imaging, to

obtain information on cartilage, see Alexander, et al., WO 02/22014. Thus, in

preferred embodiments, the measurements obtained are based on three-dimensional

images obtained of the joint as described in Alexander, et al., WO 02/22014 or

sets of two-dimensional images ultimately yielding 3D information.

Two-dimensional, three-dimensional images, or maps, of the cartilage alone or

in combination with a movement pattern of the joint, e.g. flexion-extension,

translation and/or rotation, can be obtained. Three-dimensional images can

include information on movement patterns, contact points, contact zone of two

or more opposing articular surfaces, and movement of the contact point or zone

during joint motion. Two and three-dimensional images can include information

on biochemical composition of the articular cartilage. In addition, imaging

techniques can be compared over time, for example to provide up-to-date

information on the shape and type of repair material needed.

[0087]

Any of the imaging

devices described herein can also be used intra-operatively (see, also below),

for example using a hand-held ultrasound and/or optical probe to image the

articular surface intra-operatively.

[0088]

B. Intraoperative

Measurements

[0089]

Alternatively, or in

addition to, non-invasive imaging techniques described above, measurements of

the size of an area of diseased cartilage or an area of cartilage loss,

measurements of cartilage thickness and/or curvature of cartilage or bone can

be obtained intraoperatively during arthroscopy or open arthrotomy.

Intraoperative measurements may or may not involve actual contact with one or

more areas of the articular surfaces.

[0090]

Devices suitable for

obtaining intraoperative measurements of cartilage or bone or other articular

structures, and to generate a topographical map of the surface include but are

not limited to, Placido disks and laser interferometers, and/or deformable

materials or devices. (See, for example, U.S. Pat. No. 6,382,028 to Wooh et

al., issued May 17, 2002; U.S. Pat. No. 6,057,927 to Levesque et al., issued

May 2, 2000; U.S. Pat. No. 5,523,843 to Yamane et al. issued Jun. 4, 1996; U.S.

Pat. No. 5,847,804 to Sarver et al. issued Dec. 8, 1998; and U.S. Pat. No.

5,684,562 to Fujeda, issued Nov. 4, 1997).

[0091]

FIG.

3 A illustrates a Placido disk of concentrically arranged circles of

light. The concentric arrays of the Placido disk project well-defined circles

of light of varying radii, generated either with laser or white light

transported via optical fiber. The Placido disk can be attached to the end of

an endoscopic device (or to any probe, for example a hand-held probe) so that

the circles of light are projected onto the cartilage surface. FIG.

3B illustrates an example of a Placido disk projected onto the surface of

a fixed curvature. One or more imaging cameras can be used (e.g., attached to

the device) to capture the reflection of the circles. Mathematical analysis is

used to determine the surface curvature. The curvature can then, for example,

be visualized on a monitor as a color-coded, topographical map of the cartilage

surface. Additionally, a mathematical model of the topographical map can be

used to determine the ideal surface topography to replace any cartilage defects

in the area analyzed. This computed, ideal surface can then also be visualized

on the monitor such as the 3-dimensional thickness map shown in FIG. 2, and can

be used to select the curvature of the surfaces of the replacement material or

regenerating material.

[0092]

FIG. 4 shows a

reflection resulting from the projection of concentric circles of light

(Placido disk) on each femoral condyle, demonstrating the effect of variation

in surface contour on reflected circles.

[0093]

Similarly a laser

interferometer can also be attached to the end of an endoscopic device. In

addition, a small sensor can be attached to the device in order to determine

the cartilage surface or bone curvature using phase shift interferometry,

producing a fringe pattern analysis phase map (wave front) visualization of the

cartilage surface. The curvature can then be visualized on a monitor as a color

coded, topographical map of the cartilage surface. Additionally, a mathematical

model of the topographical map can be used to determine the ideal surface

topography to replace any cartilage or bone defects in the area analyzed. This

computed, ideal surface, or surfaces, can then be visualized on the monitor,

and can be used to select the curvature, or curvatures, of the replacement

cartilage.

[0094]

One skilled in the

art will readily recognize that other techniques for optical measurements of

the cartilage surface curvature can be employed without departing from the

scope of the invention. For example, a 2-dimentional or 3-dimensional map, such

as that shown in FIG. 5 and FIG. 6 can be generated.

[0095]

Mechanical devices

(e.g., probes) can also be used for intraoperative measurements, for example,

deformable materials such as gels, molds, any hardening materials (e.g.,

materials that remain deformable until they are heated, cooled, or otherwise

manipulated). See, e.g., WO 02/34310 to Dickson et al., published May 2, 2002.

For example, a deformable gel can be applied to a femoral condyle. The side of

the gel pointing towards the condyle can yield a negative impression of the

surface contour of the condyle. The negative impression can then be used to

determine the size of a defect, the depth of a defect and the curvature of the

articular surface in and adjacent to a defect. This information can be used to

select a therapy, e.g. an articular surface repair system. In another example,

a hardening material can be applied to an articular surface, e.g. a femoral

condyle or a tibial plateau. The hardening material can remain on the articular

surface until hardening has occurred. The hardening material can then be

removed from the articular surface. The side of the hardening material pointing

towards the articular surface can yield a negative impression of the articular

surface. The negative impression can then be used to determine the size of a

defect, the depth of a defect and the curvature of the articular surface in and

adjacent to the defect. This information can then be used to select a therapy,

e.g. an articular surface repair system. In some embodiments, the hardening

system can remain in place and form the actual articular surface repair system.

[0096]

In certain

embodiments, the deformable material comprises a plurality of individually

moveable mechanical elements. When pressed against the surface of interest,

each element can be pushed in the opposing direction and the extent to which it

is pushed (deformed) can correspond to the curvature of the surface of

interest. The device can include a brake mechanism so that the elements are

maintained in the position that conforms to the surface of the cartilage and/or

bone. The device can then be removed from the patient and analyzed for

curvature. Alternatively, each individual moveable element can include markers

indicating the amount and/or degree it is deformed at a given spot. A camera

can be used to intra-operatively image the device and the image can be saved

and analyzed for curvature information. Suitable markers include, but are not

limited to, actual linear measurements (metric or imperial), different colors

corresponding to different amounts of deformation and/or different shades or

hues of the same color(s). Displacement of the moveable elements can also be

measured using electronic means.

[0097]

Other devices to measure

cartilage and subchondral bone intraoperatively include, for example,

ultrasound probes. An ultrasound probe, preferably handheld, can be applied to

the cartilage and the curvature of the cartilage and/or the subchondral bone

can be measured. Moreover, the size of a cartilage defect can be assessed and

the thickness of the articular cartilage can be determined. Such ultrasound

measurements can be obtained in A-mode, B-mode, or C-mode. If A-mode

measurements are obtained, an operator can typically repeat the measurements

with several different probe orientations, e.g. mediolateral and

anteroposterior, in order to derive a three-dimensional assessment of size,

curvature and thickness.

[0098]

One skilled in the

art will easily recognize that different probe designs are possible using the

optical, laser interferometry, mechanical and ultrasound probes. The probes are

preferably handheld. In certain embodiments, the probes or at least a portion

of the probe, typically the portion that is in contact with the tissue, can be

sterile. Sterility can be achieved with use of sterile covers, for example

similar to those disclosed in WO 99/08598A1 to Lang, published Feb. 25, 1999.

[0099]

Analysis on the

curvature of the articular cartilage or subchondral bone using imaging tests

and/or intraoperative measurements can be used to determine the size of an area

of diseased cartilage or cartilage loss. For example, the curvature can change

abruptly in areas of cartilage loss. Such abrupt or sudden changes in curvature

can be used to detect the boundaries of diseased cartilage or cartilage

defects.

[0100]

II. Single Surface

Assessment of a Joint

[0101]

Turning now to FIG.

7 A, a block diagram is provided showing steps for performing a single

surface assessment of the joint. As with FIG. 1A and B an image

or measurement is obtained of the target joint 60. Thereafter a

measurement is taken to assist in selecting an appropriate device to correct

the defect 70. The measuring or imaging steps can be repeated as

desired to facilitate identifying the most appropriate device 80 to

repair the defect. Once the measurement or measurements have been taken, a

device is selected for correcting the defect 90. In this instance,

only one surface of the joint is replicated. This technique is particularly

useful for implants that include mechanisms for anchoring the implant into the

bone. Thus, the implant has at least one surface that replicates a joint

surface with at least a second surface that communicates with some or all of

the articular surface or bone of the damaged joint to be repaired.

[0102]

As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, the practitioner can proceed directly

from the step of measuring the joint defect 70 to the step of

selecting a suitable device to repair the defect 90 as shown by

the arrow 38. Further any, or all, of the steps of obtaining a

measurement of a target joint 60, measuring a joint defect 70,

identifying device suitable to repair the defect 80, selecting a

device to repair the defect 90, can be repeated one or more

times 61, 71, 81, 91, as desired.

[0103]

Similar to the flow

shown above, following the selection of a device to repair

the defect 90, the steps of obtaining a measurement of a target

joint 60, measuring a joint defect 70, identifying device suitable

to repair the defect 80, can be repeated in series or parallel as

shown by the flow 65, 66, 67.

[0104]

FIG.

7 B shows an alternate method. A block diagram is provided showing

steps for performing a single surface assessment of the joint. As with FIG.

1A and B an image or measurement is obtained of the target

joint 60. Thereafter a measurement is taken to assist in selecting an

appropriate device to correct the defect 70. The measuring or imaging

steps can be repeated 71 as desired to facilitate identifying the

most appropriate device 80 to repair the defect. Once the

measurement or measurements have been taken, a device is manufactured for

correcting the defect 92.

[0105]

As will be

appreciated by those of skill in the art, the practitioner can proceed directly

from the step of measuring the joint defect 70 to the step of

manufacturing a device to repair the defect 92 as shown by

the arrow 39. Further any, or all, of the steps of obtaining a

measurement of a target joint 60, measuring a joint defect 70,

identifying device suitable to repair the defect 80, manufacturing a

device to repair the defect 92, can be repeated one or more

times 61, 71, 81, 93, as desired.

[0106]

Similar to the flow

shown above, following the manufacture of a device to repair

the defect 92, the steps of obtaining a measurement of a target

joint 60, measuring a joint defect 70, identifying device

suitable to repair the defect 80, can be repeated in series or

parallel as shown by the flow 76, 77, 78.

[0107]

Various methods are

available to facilitate the modeling the joint during the single surface

assessment. For example, using information on thickness and curvature of the

cartilage, a model of the surfaces of the articular cartilage and/or of the

underlying bone can be created for any joint. The model representation of the

joint can be in one, two, or three dimensions. It can include a physical model.

This physical model can be representative of a limited area within the joint or

it can encompass the entire joint.

[0108]

More specifically,

in the knee joint, the physical model can encompass only the medial or lateral

femoral condyle, both femoral condyles and the notch region, the medial tibial

plateau, the lateral tibial plateau, the entire tibial plateau, the medial

patella, the lateral patella, the entire patella or the entire joint. The

location of a diseased area of cartilage can be determined, for example using a

3D coordinate system or a 3D Euclidian distance transform as described in WO

02/22014 to Alexander, et al. or a LaPlace transform.

[0109]

In this way, the

size of the defect to be repaired can be accurately determined. As will be

apparent, some, but not all, defects can include less than the entire

cartilage. The thickness of the normal or only mildly diseased cartilage

surrounding one or more cartilage defects is measured. This thickness

measurement can be obtained at a single point or a plurality of points. The

more measurements that are taken, the more refined and accurate the measurement

becomes. Thus, measurements can be taken at, for example, 2 points, 4-6 points,

7-10 points, more than 10 points or over the length of the entire remaining

cartilage. Two-dimensional and three-dimensional measurements can be obtained.

Furthermore, once the size of the defect is determined, an appropriate therapy

(e.g., implant or an implant replacing an area equal to or slightly greater

than the diseased cartilage covering one or more articular surfaces) can be

selected such that as much as possible of the healthy, surrounding tissue is

preserved.

[0110]

Alternatively, the

curvature of the articular surface or the underlying bone can be measured to

design and/or shape the repair material. In this instance, both the thickness

of the remaining cartilage and the curvature of the articular surface can be

measured to design and/or shape the repair material. Alternatively, the

curvature of the subchondral bone can be measured and the resultant

measurement(s) can be used to design, produce, select and/or shape a cartilage

replacement material.

[0111]

III. Joint Devices

[0112]

The present device

is a prosthesis. The form of the prosthesis or device is determined by

projecting the contour of the existing cartilage and/or bone to effectively

mimic aspects of the natural articular structure. The device substantially

restores the normal joint alignment and/or provides a congruent or

substantially congruent surface to the original or natural articular surface of

an opposing joint surface that it mates with. Further, it can essentially

eliminate further degeneration because the conforming surfaces of the device

provide an anatomic or near anatomic fit with the existing articular surfaces

of the joint. Insertion of the device is done via a small (e.g., 3 cm to 5 cm)

incision and no bone resection or mechanical fixation of the device is

required. However, as will be appreciated by those of skill in the art,

additional structures can be provided, such as a cross-bar, fins, pegs, teeth

(e.g., pyramidal, triangular, spheroid, or conical protrusions), or pins, that

enhance the devices' ability to seat more effectively on the joint surface.

Osteophytes or other structures that interfere with the device placement are

easily removed. By occupying the joint space in an anatomic or near anatomic

fit, the device improves joint stability and restores normal or near normal

mechanical alignment of the joint.

[0113]

The precise

dimensions of the devices described herein can be determined by obtaining and

analyzing images of a particular subject and designing a device that

substantially conforms to the subject's joint anatomy (cartilage and/or bone)

while taking into account the existing articular surface anatomy as described

above. Thus, the actual shape of the present device can be tailored to the individual.

[0114]

A prosthetic device

of the subject invention can be a device suitable for minimally invasive,

surgical implantation without requiring bone resection. The device can, but

need not be, affixed to the bone. For example, in the knee the device can be

unicompartmental, i.e., positioned within a compartment in which a portion of

the natural meniscus is ordinarily located. The natural meniscus can be

maintained in position or can be wholly or partially removed, depending upon

its condition. Under ordinary circumstances, pieces of the natural meniscus

that have been torn away are removed, and damaged areas can be trimmed, as

necessary. Alternatively, all of the remaining meniscus can be removed. This

can be done via the incision used for insertion of the device. For many of the

implants, this can also be done arthroscopically making an incision that is

1-15 cm in length, but more preferably 1-8 cm in length, and even more

preferably 1-4 cm.

[0115]

The implants

described herein can have varying curvatures and radii within the same plane,

e.g. anteroposterior or mediolateral or superoinferior or oblique planes, or

within multiple planes. In this manner, the articular surface repair system can

be shaped to achieve an anatomic or near anatomic alignment between the implant

and the implant site. This design not only allows for different degrees of

convexity or concavity, but also for concave portions within a predominantly

convex shape or vice versa. The surface of the implant that mates with the

joint being repaired can have a variable geography that can be a function of

the physical damage to the joint surface being repaired. Although, persons of

skill in the art will recognize that implants can be crafted based on typical

damage patterns. Implants can also be crafted based on the expected normal

congruity of the articular structures before the damage has occurred.

[0116]

Moreover, implants

can be crafted accounting for changes in shape of the opposing surfaces during

joint motion. Thus, the implant can account for changes in shape of one or more

articular surface during flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, rotation,

translation, gliding and combinations thereof.

[0117]

The devices

described herein are preferably marginally translatable and self-centering.

Thus, during natural articulation of a joint, the device is allowed to move

slightly, or change its position as appropriate to accommodate the natural

movement of the joint. The device does not, however, float freely in the joint.

Further, upon translation from a first position to a second position during

movement of a joint, the device tends to returns to substantially its original

position as the movement of the joint is reversed and the prior position is

reached. As a result, the device tends not to progressively “creep” toward one

side of the compartment in which it is located. The variable geography of the

surface along with the somewhat asymmetrical shape of the implant facilitates

the self-centering behavior of the implant.

[0118]

The device can also

remain stationary over one of the articular surface. For example, in a knee

joint, the device can remain centered over the tibia while the femoral condyle

is moving freely on the device. The somewhat asymmetrical shape of the implant

closely matched to the underlying articular surface helps to achieve this kind

of stabilization over one articular surface.

[0119]

The motion within

the joint of the devices described herein can optionally, if desired, be

limited by attachment mechanisms. These mechanisms can, for example, allow the

device to rotate, but not to translate. It can also allow the device to

translate in one direction, while preventing the device from translating into