An excerpt from the article by Morris H. Dislocations of the Thigh: their mode of occurrence as indicated by experiments, and the Anatomy of the Hip-joint (1877, pp. 161-170). The author noted that the ligamentum capitis femoris (LCF) is stretched during flexion, adduction, and external rotation. It was found that the LCF is always damaged in hip dislocations, is more often torn from the femur, and is rarely ruptured. Discussion of article see article 1877BrookeC.

DISLOCATIONS OF THE THIGH: THEIR MODE OF OCCURRENCE AS INDICATED BY

EXPERIMENTS AND THE ANATOMY OF THE HIP-JOINT.

BY HENRY MORRIS, M.A., M.B., F.R.C.S., ASSISTANT SURGEON TO, AND

LECTURER ON ANATOY1 AT, THE MIDDLESEX HOSPITAL.

Received January 9th-Read February 13th, 1877.

RECENTLY, whilst making various dissections of the hip-joint, the

usually accepted doctrine that dorsal and ischiatic dislocations of the femur

occur when the thigh is in a position of adduction appeared to me as very improbable,

on anatomical grounds alone, and I was, therefore, led to test the truth of it

my means of experiments on the dead body.

I propose in the following remarks to prove by anatomy, experimental

results, and clinical facts-(I) that all kinds of dislocations at the hip-joint

can take place while the thigh is abducted; (2) to give reasons for believing

that abduction is the position in which all dislocations of the thigh happen;

and (3) to show that in any given case the dislocation will be backwards, downwards,

or forwards, according as flexion with rotation inwards, or extension, or

extension with rotation outwards, is associated with abduction at the moment of

accident; or is provoked by the same violence which produces the displacement.

First, I will state briefly the anatomical features which bear upon the

question.

The acetabulum looks forwards as well as outwards and downwards, and

receives the head of the femur, which also looks forwards. The thickest and

strongest part of the innominate bone is that which forms the upper and posterior

wall of the acetabulum; it is this part of the bone which enters into the

formation of the weight-bearing arches of the pelvis, viz. of the pelvic brim, along

which the weight is transmitted to the heads of the thigh bones in the upright

and stooping positions, and of the vertical or ischial arch, along which the

weight is transmitted to the tuberosity of the ischium in the sitting posture.

This same part of the innominate bone forms by far the deepest portion of the

acetabulum, the articular surface of which is fully an inch wide in its iliac

portion, and nearly as wide in the ischial. Along the lower part of the

acetabulum, on the other hand, the articular facet, so far as it exists at all,

is very narrow; while the cotyloid notch intercepts the rim for nearly one inch.

The head of the femur presents a much larger articular surface above the

transverse plane through its centre than below it. The measurement (in a

horizontal plane), from a vertical line skirting the dimple for the round ligament

to the outer limit of the articular surface on the upper aspect of an average

femur, is an inch and two thirds; whereas to the outer border of the articular

surface below is only three eighths of an inch. The notch for the round ligament

is in the lower and posterior quarter of the head; the most prominent point in

the head is below this notch, while the part above slopes off from within outwards.

As a consequence of all this, when the thigh is flexed and adducted, the most

projecting part of the head passes into the deepest part of the acetabulum and presses

against the broadest and strongest part of its wall; whereas in abduction this

prominent part of the head of the femur projects beyond the lower part of the socket

at the cotyloid notch.

THE LIGAM1ENTS. It is only necessary to refer to two of the four

ligaments of the joint, viz. the capsular and the round ligament.

The capsular ligament is large and loose, so that in every position of

the limb some portion of it is relaxed. In thickness and strength it varies

greatly in different parts; thus if two lines be drawn, one from the anterior inferior

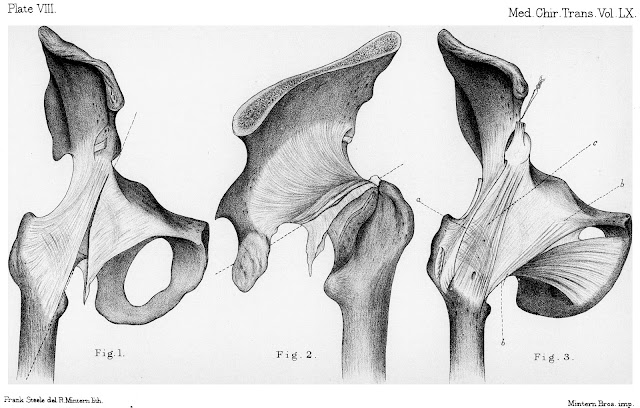

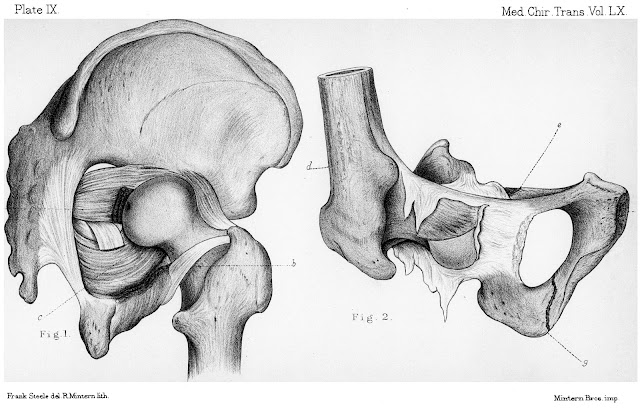

iliac spine to the inner border of the femur near the small trochanter (Plate

VIII, fig. 1), the other from the upper border of the tuber ischii to the

digital fossa (Plate VIII, fig. 2), the ligament above and behind these lines,

is very strong; whereas all below, except along the narrow pectineo-femoral

band, is very thin and weak, sometimes permitting the head of the bone to be

seen through it. There are three bands auxiliary to the capsule, or more correctly

speaking, three portions of the capsule, which have received separate names,

and which for the sake of description are called ligaments, although it would

be erroneous to suppose that either of these bands or ligaments are structures

separate from the capsule. The best known of them is the ilio-femoral ligament,

a large triangular mass of coarse, well-marked fibres, the broadest end of

which is at the femur (Plate VIII, fig. 3). Its fibres are somewhat accumulated

both along the outer and inner sides of the femoral attachment, while several

curved intercolumnar fibres, which spring from the centre of the capsule, pass

to the femur with the inner set.

This arrangement of the fibres has led to the ligament being called by

some the "inverted Y-shaped ligament," and exaggerated

representations of it, in accordance with this name, have been drawn. Such, for

instance, are the diagrams of the ligament in Bigelow's work and in the works

of those who have copied therefrom. The name is, however, inappropriate, for

although the double accimulation of fibres may be made, by dissection, to show

somewhat the appearance of an inverted Y, there is not any natural interval

between the two imaginary arms of the ligament beyond a small aperture for the

entrance of a branch of the external circumflex artery into the joint. Except

for this small opening, the strong central fibres which take a straight course

to the femur are not interrupted, and are of considerable thickness. The

mistake has arisen, I imagine, from the presence of two well-marked bands

connected with the surface of the capsule along the upper and outer border of

the ilio-femoral ligament. One of these, the shorter and posterior, passes to

the tendon of the gluteus minimus from the middle of the capsule; the other,

not hitherto described, but generally well marked, extends from the vastus

externus to the long head of the rectus femoris, and moves with both these

tendons (Plate VIII, fig. 3). The latter especially gives the appearance of a superadded

outer arm to the ilio-femoral ligament, while the more oblique direction of the

inner fibres completes the supposed Y-shaped outline.

The ischio-femoral ligament extends from the ischial border of the

acetabulum to the upper and back part of the neck of the femur, just internal

to the highest part of the digital fossa. When the thigh is flexed the fibres

of this ligament pass almost straight to their femoral insertion, and are

spread out uniformly over the head of the femur, but in extension they wind

upwards and outwards to the femur in a zonular manner (Plate VIII, fig. 2), and

form quite a thick roll along their lower border. The upper and back part of

the capsule between the ilio-femoral and ischio-femoral ligaments is very

strong and thick, although not so strong and thick as the ilio-femoral itself.

The latter is as stout as the tendo Achillis, and is often more than a quarter

of an inch in thickness; the rest of the strong part of the capsule varies down

to one eighth of an inch or a little less in thickness.

The third auxiliary band is the pectineo-femoral ligament (Plate VIII,

fig. 3), a distinct but narrow set of fibres, extending from the pubis and

pubic border of the cotyloid notch to the lower and back part of the neck of

the femur just above the small trochanter.

The effect of these bands on movements of the hip-joint is as follows:

The ilio-femoral supports the trunk in the erect posture by limiting extension;

it is made tense throughout in every position of extension, except when extension

is combined with abduction, and then the outer fibres are relaxed.

The ischio-femoral band does not limit simple flexion, but is tight

during flexion combined with adduction, and flexion combined with rotation

inwards. In extension, in flexion with rotation outwards, and in abduction, it

is quite loose. The part of the capsule between the ilio- and ischio-femoral

ligaments assists the former in limiting simple extension; it is also made

tense in extension with adduction, but is most tense in adduction combined with

slight flexion, - the stand-at-ease position.

The pectineo-femoral ligament is stretched in every position of flexion

and of extension when associated with abduction. It is the structure which

limits abduction, and is especially tight during abduction combined with slight

flexion, and also when marked flexion with outward rotation accompanies

abduction.

The ligamentum teres, so far as its attachments are concerned, needs no

notice here, but its action and use require a word or two. Without discussing

the differences of opinion which have been expressed on these points it will be

sufficient to state, as the result of several examinations, that the ligament

is most tight during flexion combined with adduction and rotation outwards, but

that it is also tight, though to a less degree, during flexion with rotation

outwards, as well as during flexion with adduction. As the thigh passes from a

position of adduction with flexion to one of adduction with extension it

becomes less and less tense, and is quite lax when full extension is reached.

In every position of abduction it is loose, while in abduction associated with

simple flexion it is at its loosest, and the ligament is then folded upon

itself so completely as to have its femoral and acetabular attachments on the same

level and opposite to one another.

From a consideration of these anatomical facts, it is evident that no

conditions of the joint can be more favorable to rupture of the capsule and

dislocation of the thigh than those of abduction. In abduction the head of the femur

is more than half out of the acetabulum, bulging over the transverse ligament;

the cotyloid notch being filled with soft compressible fat allows the ligament

to yield a little as the head of the bone is forced over it; and the most

prominent part of the head of the femur is resting hard against the thin

portion of the capsule. This part of the capsule is strengthened somewhat by

the pectineo-femoral ligament it is true, but it derives no appreciable support

from muscles as does the rest of the capsule. The ligamentum teres, being quite

loose, is absolutely powerless to resist force, but is most favorably situated

to snap under a sudden jerk. Finally, in abduction all the strong portion of

the capsule is relaxed, excepting during complete extension, when the innermost

fibres of the ilio-femoral ligament become tense. In fact, it may be 8aid that

there is a natural tendency for the head of the femur to be displaced during

abduction of the thigh.

Nor is there any other position so favorable to dislocation as

abduction. It is quite unnecessary to discuss the improbability of dislocation

in positions of simple extension, when the ilio-femoral ligament is the

resisting structure; it is only in the rarest, i.e. the so-called irregular

dislocations, that this part of the capsule is ever ruptured, and even then

only by the extension of the laceration commenced elsewhere, and the peeling

off of the ligament from its bony connections.

There is, however, a pretty prevalent opinion that dorsal dislocations take

place during adduction through a rent in the upper and back portion of the

capsule, and that the use of the round ligament is to resist forces which tend

to drive the bone out in this direction. Now, as dorsal dislocations are more

common than all the others put together, it is most likely that they occur

through some strain upon the weak part of the capsule, and it is necessary to

state the anatomical provisions against their occurring during adduction. It is

only during flexion with marked adduction, and flexion with rotation inwards, that

the head of the femur presses firmly against the upper and back part of the

capsule, and even in these positions the most prominent part of the head is

against the strongest and deepest side of the acetabulum. Daring flexion with

adduction the ligamentum teres is on stretch, and therefore in action to resist

displacing forces, so far as it ever can do so. The portion of the capsule

against which the head of the bone is bulging is strengthened by various

muscles, and these during adduction and inward rotation lie stretched over it;

the most important of them is the obturator internus, which, when stretched,

acts much like a ligament on account of the several tendons into which the

muscular tissue is inserted and the connection of some of the ultimate fibres

of these tendons with the bony origin of the muscle; the power of resistance of

this muscle is increased too by the play of the tendons of the trochlear groove

of the ischium, whereby the strain on the muscle is diminished. Finally, the

close connection between the external rotator muscles, as they pass to their

insertions, and also of the gluteus minimus, with the capsule, must strengthen

and support the upper and back part of that ligament.

Thus, the anatomy of the joint, it seems to me, points to abduction as

the only position in which dislocation of the thigh can possibly occur.

Experiments upon the dead body confirm the conclusion suggested by anatomy. They

also establish the fact that all the regular varieties of dislocation of the

hip can be produced and reduced after the head of the femur has been displaced

in abduction. It will be best at once to state that the only way in which I

have been able to dislocate the thigh is by forcibly abducting it. I have

tried, standing over the body, the pelvis of which has been firmly fixed by two

men, to force the bone out of the acetabulum through the back of the capsule; I

have removed all the muscles and tried the same thing when only the capsule and

wall of acetabulum were left to resist, and when, by previously flexing and

adducting, or flexing and rotating inwards the thigh, the strain upon the

capsule is at its greatest. I have also tried, by bringing the legs across one

another, and jerking and forcing the thigh with the whole leverage of the limb

to assist me, as well as by striking with a heavy block the front and outer

side of the knee, to dislocate the flexed and adducted thigh; but by none of these

means have I ever once succeeded.

As soon, however, as the limb is abducted and jerking force is applied

to it while in that position, the head of the femur bursts through the capsule,

and the dimple for the round ligament can be felt beneath the skin of the perinaeum.

After the head has left the acetabulum it can be made to pass either towards

the dorsum ilii or the ischiatic notch by flexing and rotating the limb inwards

more or less; or on to the pubis by extending and rotating it outwards.

The following statements are based on fifteen experiments:

The results in all these cases were so similar that it seemed

unnecessary to record the notes of more. Except when specially stated to the

contrary all the dislocations were effected before any dissection whatever was

commenced.

1. The rent in the capsule varied with the degree to which the upward

displacements had been carried previous to dissection, but it was always

limited to the thin portion of the capsule. In none did it involve the

ilio-femoral or the ischio-femoral ligament, or the strong part of the capsule

between them. In most cases it commenced at the pubis, ran obliquely downwards

and backwards to the neck of the femur, and then extended upwards to a greater

or less distance towards the digital fossa, either peeling the capsule from the

back of the neck of the femur or tearing it through at a short way from its attachment

to that bone (Plate VIII, figs. 1, 2). In some cases the periosteum was torn

away with the ligament from the pubic part of the acetabulum, and in one the

whole of the under and inner side of the capsule was separated from the

acetabular margin; but in all, the rent took the same general course along the

femoral insertion of the capsule.

2. The ligamentum teres was ruptured in every case by the dislocating

force, and not by the subsequent movements whereby the dorsal or other

positions were obtained. This was ascertained by feeling for the dimple in the

head through the periraeum. In all but three the ligament was detached from the

femur, and with it, in some instances, a scale of articular cartilage. In three

cases it was torn asunder, once near the femur and twice near its middle.

3. The pectineus, quadratus femoris, and external obturator muscles were

ruptured, the two former in every case, the latter each time it was examined.

The gemellus inferior was generally torn asunder.

4. The obturator internus was ruptured in two instances, and the

adductors longus and brevis in one and the same case. In none was the neck of

the femur embraced by the small rotator muscles (viz. gemelli, obturator

internus, and pyriformis); nor could the head of the bone be made to pass

upwards beneath the obturator internus tendon, i. e. between it and the capsule

of the joint, but it could be forced upwards onto the dorsum over the posterior

surface of the muscle.

5. In no case was the ilio-psoas or the gluteus minimus ruptured. In one

of the cases in which the obturator internus was torn the pyriformis and the

lower border of the gluteus medius were also lacerated.

6. In three cases the great sciatic nerve was lying in front of the neck

of the bone, and was not seen in the dissection of the gluteal region until the

dislocation was reduced. In one case the nerve was carried before the neck and

retained there after reduction.

7. In three cases the dislocation' was compound,' so that the head of

the femur protruded through the skin of the perinaeum.

…

External links

Morris H. Dislocations of the Thigh: their mode of occurrence as indicated by experiments, and the Anatomy of the Hip-joint. Medico-Chirurgical Transactions. 1877;60:161-186.1. [pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]

Brooke C. Dislocations of the Thigh: their mode of occurrence as indicated by experiments, and the Anatomy of the Hip-joint. By Henry Morris. M.A., M.B. Reports of Societies. Br Med J. 1877Feb17;1(842):203. [pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov]

Authors & Affiliations

Henry Morris (1844-1926) was a British medical doctor and surgeon. [wikipedia.org]

|

| Sir Henry Morris (before 1915) Author Anton Mansch, published by A. Eckstein, Berlin; original in the wikimedia.org collection (CC0 – Public Domain, no changes). |

Keywords

ligamentum capitis femoris, ligamentum teres, ligament of head of femur, role, dislocation, injury, damage

NB! Fair practice / use: copied for the purposes of criticism, review, comment, research and private study in accordance with Copyright Laws of the US: 17 U.S.C. §107; Copyright Law of the EU: Dir. 2001/29/EC, art.5/3a,d; Copyright Law of the RU: ГК РФ ст.1274/1.1-2,7

Comments

Post a Comment